The Fantasy of Free Electricity From Surplus Wind Power

Using surplus wind energy to produce hydrogen seems like a simple, cheap way to decarbonize, but in reality it is not viable without massive subsidies. Read on:

The more wind power you have, the more expensive it becomes.

One of the often-ignored aspects of wind power is that you cannot reach more than about 35% of your total grid power from wind without curtailing that power during periods of high wind and low demand. As more wind power is added to a grid the amount of curtailment increases. Countries that achieve higher percentages of wind power are connected to neighboring grids that can accept the surplus, but what happens when the neighbors also have surplus wind power?

Obviously, as more wind turbines are added the curtailment will increase, and that will push up the cost of the usable wind power.

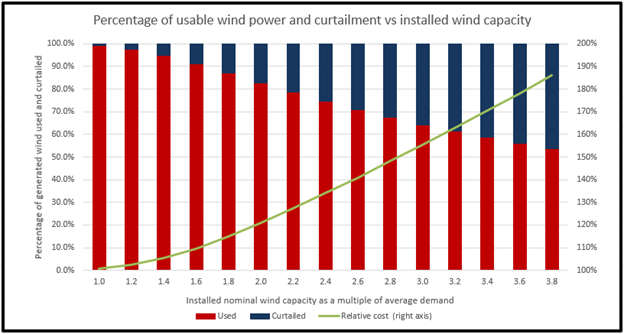

This is how it looks in a wind-dominated grid without imports and exports:

The X-axis is the installed wind power as a multiple of average demand, the red bar is the wind energy that can be used and the blue bars are curtailed energy. The green line shows how the cost climbs as more turbines are added.

Wind only generates about 40% of its nominal capacity, so you need 2.5 times the installed capacity to generate an amount of energy equal to the demand. If you have a grid that is relying on wind, a nominal capacity of 2.5 times the average demand will be capable of providing all the needed energy, but not at the right time. As you can see, at that point about 25% of the available power will have to be curtailed and only 75% of the energy that could be generated is usable. At that point, the grid is still a long way from a net zero target without the addition of expensive and inefficient storage, and the cost of usable wind energy will have risen by about 33%.

Adding another wind turbine at that point increases the curtailment of all the other turbines, it only contributes about 30% of its own nominal capacity and it has an incremental cost of more than 3 times that of the early turbines. Adding more wind turbines becomes very expensive, soon reaching the point where it becomes non-viable but never reaching net zero.

Hydrogen as the solution

One of the suggested solutions to this problem is using surplus wind power to make hydrogen using electrolysis.

However, electrolysis is a very inefficient and expensive way of making hydrogen, that’s why most hydrogen today is made from natural gas by steam methane reforming (SMR).

SMR is more efficient than electrolysis and if the power for electrolysis comes from fossil fuels, the CO2 emissions are higher than those from the SMR process, three times higher if the power comes from natural gas and five times higher if the power comes from coal. To be considered “green” the hydrogen plant must get almost all its wind from low-carbon sources.

Proponents of wind power claim that cheap hydrogen can be made using surplus wind power. Because the power would otherwise be curtailed, they argue that it can be provided at zero cost to the electrolysis plant.

However, hydrogen plants are not free, electrolyzers cost about $1200/Kw and the plant must also include water treatment, power transformers and rectifiers, hydrogen separation and drying, compressors, and storage. Production will be highly variable, so large volumes of storage will be needed to meet a continuous demand. Total costs are likely to be in the region of $2,000/Kw. Amortizing that cost over a 25-year life at 8% would require an income of $200/Kw/year to pay back the invested capital.

A 1 Kw electrolyzer can make about 168 Kg of hydrogen per year at full utilization, so paying pack the capex needs $1.19/Kg if the plant is operated at full capacity, and $2.38 if it is operated at 50% capacity.

For a plant that achieves 50% utilization, operating and maintenance costs will add another $0.30, bringing to cost to $2.68 plus the cost of electricity. About 55 kWh of electricity is needed to make 1 Kg of hydrogen, so electricity at $0.08 per kWh would increase the hydrogen cost to more than $7/Kg.

For transportation use, the cost to the end user would be significantly higher because of the infrastructure required and the high cost of distributing the hydrogen.

The chart below, from a study produced for the Hydrogen Council, shows the hydrogen price that would be competitive against low-carbon alternatives for various proposed applications.

As you can see, many of the applications are not competitive unless the hydrogen is below $3, but to get the cost down that low the electricity would have to be free or very cheap.

Let’s see how that would fit into our wind-powered grid. The hydrogen plant can use surplus power from the grid. In fact, that’s the only way the hydrogen should be considered “green” because if the power is not surplus, then it can be used elsewhere on the grid or exported to a neighboring grid to reduce fossil fuel use. Even hydrogen purchased directly from a wind or solar facility cannot be truly “green” if it is simply diverting power from a grid and forcing other users to make up the difference from fossil fuels. And that statement holds true, even if the wind or solar facility is an addition to the grid.

However, there must be enough surplus wind power for the hydrogen plant to achieve its target capacity factor. This is how it would look if the target is a 50% utilization:

There isn’t enough surplus wind to achieve the 50% capacity factor until you have installed wind turbines with a nominal capacity equivalent to 2.8 times the average demand. At that point, curtailment exceeds 30% and your 8 cents wind power has become 12 cents. If you want to install more electrolyzers and still achieve a 50% capacity factor, you must add more wind turbines. Adding more wind turbines increases the amount of surplus wind, but the ratio of surplus to usable wind doesn’t change significantly, you are still curtailing 30% of your potential turbine production.

In the far right-hand bar of the chart, the electricity grid can use only 50% of the production capacity of the wind turbines, the hydrogen plant consumes 20% and 30% is curtailed. If the power is free to the hydrogen plant, the electricity grid must pay 16 cents, double its original 8-cent cost. There is no free power, one or the other customer must pay for the cost of the turbine.

There is also considerable annual variation in the surplus wind and by implication in hydrogen production. In the 37 years of data that I used to compile the chart, the surplus wind in the windiest year was almost twice the least windy year (at the 3.0 installed capacity). To cope with that variation and supply hydrogen for transportation and industrial use continuously, storage capacity would be needed for at least 10 months of average supply. Compare that to the less than 3 weeks capacity in the world’s oil storage and you get some idea of the challenges.

In summary.

· The whole concept of free electricity to make hydrogen from surplus wind power is a fantasy.

· A hydrogen plant cannot operate economically using occasional bursts of surplus wind from a wind-powered grid, and to provide enough surplus wind for a hydrogen plant to be viable, it is necessary to add wind turbines to create the surplus.

· Supplementing the power supply from fossil fuels is expensive, and quickly overwhelms any reduction in emissions from the use of wind power to make “green” hydrogen.

· Adding more hydrogen production capacity involves adding more wind turbines, but surplus power must still be curtailed in roughly the same proportion.

· If the hydrogen plant pays a lower price for the electricity, then the cost is shifted to the consumer, it is not free electricity.

· Using hydrogen for transportation or industry requires vast amounts of storage to cope with multi-year variations in wind energy.

Based on my analysis I don’t think making hydrogen from surplus wind power will ever be viable without subsidies. I have not looked at solar, but I suspect the answer will be similar. Hydroelectric power could be used, but much of that is seasonal, and subject to variability because of drought or the need to maintain river flow. In any case, there are few places that have surplus hydropower that cannot be exported to neighboring grids to offset fossil fuel use.

The proposed subsidy regime for “green” hydrogen will probably spawn many projects that would otherwise be non-viable, leaving the taxpayer footing the bill for an enormous misallocation of capital.

A note about the data source for the charts:

The information for compiling these charts comes from

https://www.renewables.ninja/, it is a database of hourly wind and solar conditions collected over a 37-year period for multiple countries. The dataset I used was from the UK which has good wind resources, the data used is a mix of both onshore and offshore wind. Obviously, the wind is not uniform everywhere, but I think this is a reasonable indication of what can be expected in many other locations.

Hourly capacity factors for 37 years were compared against the demand for the latest year for which data was available (2019), and predictions of surplus wind availability were calculated over the 37-year period.

If you want more information about the method used, leave a note in the comments.